What is Costing Costing You?

The answer is everything. Agricultural accounting software that will allow you to understand the true costs of your sales is the key to developing strategies for growing your business in a profitable, sustainable way. While this may sound easy, it’s not, particularly in the agriculture industry, which presents a unique set of challenges. How do you develop an accurate margin when the costs of your ingredients are fluctuating or are fundamentally unknowable, sometimes even after you’ve manufactured and sold the product?

My Accounting Professor Made It Sound Easy

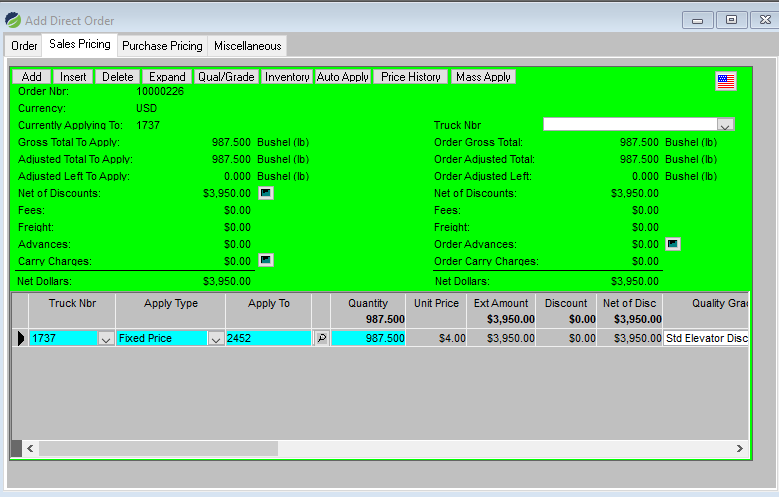

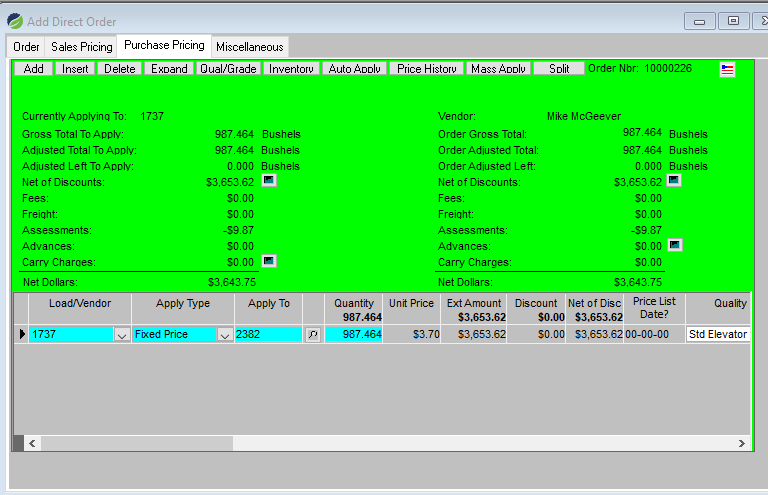

In principle, it sounds easy. You purchase inventory as an asset, and when you sell it you move the cost of the asset to the cost of goods sold. The difference between your sales price and your purchase price is your gross sales margin. Adding in your other costs (salaries, facility costs, overhead) enables you to compute the profitability of each sale, and manage your business.

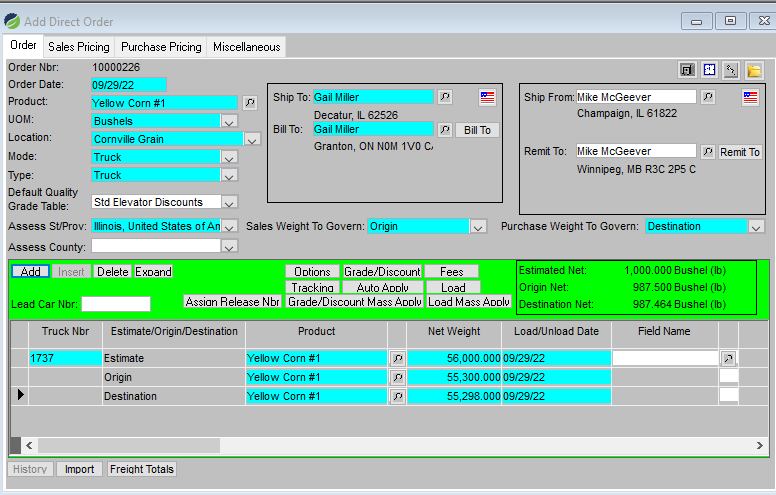

This approach works well for products with a readily known purchase cost, such as buying and selling a rake through your farm supply division. But grain accounting is far more complex, as you are also managing merchandising contracts, risk hedging, and terminal storage. Grain can be bought using unpriced contracts, where the final futures or basis price may not be known for weeks or even months after the purchase has occurred. Accounting rules also allow you to revalue products that are bought and sold in commodity markets, so the corn you bought last month can (and should) be revalued in you inventory at your current market price. Indeed, accounting for commodity inventory is much more analogous to accounting for negotiable securities like stocks, which are revalued with an unrecognized gain or loss every month.

If you are buying and selling commodities such as corn or wheat, it is valid to price them after the purchase and revalue them as market conditions change, typically at the end of a financial period. However, the problem becomes more complex when you use the product internally to manufacture other products. What is the value of the corn that you have purchased but which you haven’t paid for (and for which you don’t have a price) when that corn has been used to manufacture cornflakes?). Revaluing it (and possibly recognizing a gain in the value) doesn’t seem like a viable solution, as if you are doing feed blending sucking corn out of cornflakes and putting it back on the cob is a process beyond the scope of most grain processing facilities.

OPTION ONE: WHAT’S MINE IS MINE

One solution is to separate the risk of fluctuating commodity pricing from the manufacturing of your product. This can be accomplished by running the commodity procurement traders and the feed/manufacturing facilities as separate cost centers. Unpriced (or priced) grain can be transferred from the grain elevator to the feed/manufacturing division at the current standard cost, typically derived from the current market price. The advantage of this approach is that you segregate out the gains/losses due to good (or bad) commodity trade risk management in the grain division, without passing the gains or losses onto the feed division. So if you managed to purchase corn at $3 a bushel, and when the corn was actually transferred to the feed manufacturing division it was worth $7 a bushel, then that gain would be recognized by the traders rather than the feed division, with the grain elevator software tracking the difference.

Note that some companies allow the feed division to buy grain externally if they can find another price, or allow the grain division to sell their grain to a competitor if they can get a better price. Although this might seem non-intuitive, the goal of this approach is to create market efficiencies that drive better purchase decisions.

OPTION TWO: MARKET TILL YOU MAKE IT

Segregating purchasing and manufacturing works for businesses that run their purchasing and processing functions as separate divisions, however, there are times when it makes more sense to have a single bottom line. For example, if you are running a livestock company, or a feed manufacturing company, and purchasing grain is merely an adjunct to your core business, then your goal may be to reflect all costs in your finished product as accurately as possible, rather than to create a separate cost center for grain.

We recently completed a new module that allows us to accumulate costs – including the costs for unpriced grain – into your final inventory cost, even if the product used for manufacturing is still unpriced. This enables you to seamlessly accumulate your commodity purchase costs into the finished products costs for your feed blending or fertilizer blending. The procedure works as follows:

1) You run your grain purchasing system as a periodic inventory system. You record inventory purchase costs only when the grain is priced.

2) At the end of the period (weekly, or monthly) you bring the unpriced inventory to market. If the inventory has been used in manufacturing, then you move that cost into your finished goods inventory or cost of goods sold. Otherwise, you keep the cost as part of your raw materials inventory.

3) You would reverse out the “to market” entries, and repriced any unpriced grain at the end of the next period, until the grain is actually priced.

4) You also have the option of folding other expenses (such as your risk hedging or other commodity risk management costs) into your market price.

CONCLUSION

Computing margins for finished products that use unpriced inventory creates a unique set of challenges. Agrosoft agtech software allows you to transfer unpriced costs using a fixed market price or standard cost, or adjust the unknown cost until the purchase is complete and the price can be fixed. There is no right answer, and the choice may well depend on whether you are a grain business with a feed blending division or a livestock/feed manufacturing company with a grain division. Whatever your situation, our dedicated team of professionals is here to develop the perfect solution for you.